4 Hard Truths About Gaming Barely Anybody Acknowledges

As a sickly child deeply unpopular with my peers, I became interested in video games at an early age. And now, as a moderately healthy adult deeply unpopular with my peers, video games are my analgesic of choice for the immutable pain of existence. But one thing I don’t like about video games is the way people talk about them on the internet, which is generally a deluge of stupidity and uncalled-for racism usually only seen when googling “how to get rid of an Italian ghost.”

Maybe because of my background in film or maybe because I am just a weird little gremlin I have some -- dare I say? -- correcter subjective opinions on how videogames should be engaged with.

Graphics Don’t Matter

I am sure that simply reading that header will send some people into a frothing rage. It’s okay. I accept your disdain. It is my burden as a Promethean figure to bring the light of truth to the unwashed hordes. I have heard the Good Word, and it is this: graphics don’t matter.

If you look at any forum centered around videogaming, you’ll inevitably run into two things: people asking for advice on a boss being met with comments bragging about how they didn’t have trouble with that boss, and people screaming at each other about which $800 graphics card increases visual fidelity more. But graphics are the least important part of the gaming experience. If you go to a movie with a friend and then ask them what they thought of it and the first thing they say is that the camera clarity was incredible, also consider asking them how they enjoy converting biomass into energy via digestion and their top three favorite ways to utilize oxygen to keep their organs alive -- your friend is clearly a robot sent from the future to infiltrate humanity.

I’m not saying I don’t appreciate a game with realistic graphics, just that it’s far and away the least important thing for me as a consumer of media. I don’t get mad when I count all of the clogged pores on Ellie’s nose in The Last of Us 2. I just don’t care beyond a fleeting moment of huh, neat. Studios spent tens of millions of dollars and it evokes the same level of wonderment in me as looking out the window and seeing a bird. Realistic graphics are always a novelty, and one with a shelf-life shorter than a gallon of pigmilk forgotten in a car on a midsummer’s day. There was a time when Oblivion graphics were considered mind-blowing, holodeck-levels of realism:

Bethesda

How about a modern example? Demons’ Souls on the PS5 looks like this:

Sony Computer Entertainment

And here’s a still from The Last of Us:

Sony Computer Entertainment

Demon’s Souls looks better...but not, like, THAT much better. Those games came out about seven years apart. I think we’ve maybe reached a point of diminishing returns in terms of graphics where ever-increasing computing horsepower is getting us less and less in return. Here are two games with about as much time between them as The Last of Us and the remake of Demons’ Souls:

Nintendo

Valve

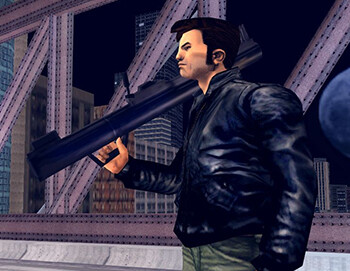

And of those two games, I’d say that in some ways the graphics of Super Mario 64 actually hold up better than those of Half-Life 2. Games with a distinctive visual style that isn’t meant to emulate reality generally age better than games that do. That’s why Claude from Grand Theft Auto III looks to modern eyes like a Soviet orphan’s treasured hand-carved potato doll…

Rockstar Games

...and why Link from The Wind Waker looks fantastic. Like, well, like a cartoon.

Nintendo

If tomorrow I was elected King of Games (it’s an elected position, yes), the first thing I would do is declare a moratorium on making graphics more realistic. I hereby declare all graphics henceforth as Good Enough. Take all that effort and put it into making better physics so we can get a VR game that really nails telekinesis or invent a videogame ladder that actually goddamn works. Actually, the first thing I would do is demand a port of Banjo-Kazooie and Banjo-Tooie to the Switch, then the graphics thing. Then probably outlaw any PvP that’s not opt-in (I am a busy adult, FromSoft, and sometimes I need to pause my game to do important shit), then make it so anyone who has unironically used the term “real gamer” can only play Dreamcast together and nothing else.

I want to make a distinction here between graphics and art direction. I’m talking about games trying to visually emulate the appearance of the real world as closely as possible object-to-object. I’m not talking about the overall aesthetic of a game world, which is, to my mind, vastly more important. Despite what forums full of angry nerds will tell you, visual realism doesn’t immediately make a game visually appealing. It’s why The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which was basically shot on an old can of beans with a hole punched in it with a screwdriver, looks goddamn amazing:

Decla-Bioscop

Whereas the airport fight scene in Captain America: Civil War was shot on a customized version of the Arri Alexa 65, a 6K 65mm beast of a camera, a barebones version of which costs over $10,000 per day to rent. If the visual fidelity in this scene was any better it would be a play. And that scene ended up looking like this:

Walt Disney Pictures

I’ll spare you any riffs I have about the above image, because this article is about games and also because I would like the nice people at Disney and all subsidiary corporations to please hire me to write on one of their many fine movies or television shows. Atmosphere and aesthetic are vastly more important to my enjoyment of a game than the realism of its graphics. It’s part of what makes a game feel like you’re exploring a full, real world -- which is really part of the fun of games to me. So much so, in fact, that it conveniently brings me to my next point.

Sometimes The Onus is On the Player to Have Fun

This entry might be a little too specific to my exact pet peeves, so let me explain what I mean. There is, in talking about games, an impulse to view them as only having value when providing explicit things for you to do. Games that constantly have a laundry list of activities aren’t always a bad thing -- just ask my hundreds of hours in Destiny, a game where you’re an immortal gun-toting space wizard that kills the same dozen or so enemies for eternity like some sort of Dante’s Inferno-ass demon. When a game is open-ended, sometimes the most fun you can have is what you, the player, can create from the game’s systems.

I enjoy linearity when it’s executed well, like in DOOM (2016). But my favorite types of games tend to be large Bethesda-style sandboxes or games with complex interlocking systems such as Dishonored. When games give the player an opportunity to be creative in their approach to play, that’s part of what makes the medium shine. That’s not something film can do. If you ask your friend their favorite part of Schindler’s List and they said the part where the leprechaun shrank the guy and he got stuck in a cheerleader’s genitals, you wouldn’t assume he watched the movie differently than you did -- you’d assume they accidentally watched the 1990 film Getting Lucky instead.

Troma Entertainment

But there’s an impulse to call any kind of open-endedness “lazy” or “bad design” if the game isn’t constantly telling the player how to play. The phrase “wide as an ocean, deep as puddle” was a trendy thing to say about The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim when it became so popular that liking it pissed off weird gaming gatekeepers. But part of the fun of games like Skyrim is the fun you make yourself. If you lack the imagination necessary to find enjoyment in the simple act of wandering around a completely alien and magical world then your heart is already a joyless husk of unspiced oatmeal recipes and STEM bumper stickers. If, when playing Fallout 4, your reaction is there’s just nothing to do! instead of Hahaha that robot I built with a flamethrower and a mini-nuke launcher to defend the multi-level trailer park city I built in the old drive-in theater can wear a cowboy hat, hahaha this game rules, maybe sandbox-style games aren’t the games for you. For me though, part of what makes games unique is that there can be an element of freedom in how they’re experienced.

To continue using Skyrim as an example, I once made a character called Two-Axe. Two-Axe was an illiterate barbarian who was looking for someone special to share his life with.

Bethesda

Because Two-Axe was illiterate, I didn’t read any notes or books in-game. If a quest required it, I’d just wander around and hope I found the right place, two-axing everything in my path. And since Two-Axe wanted to settle down, anyone who showed him kindness would be rewarded with gifts -- by which I mean I’d sneak into their houses and leave them stinking hides, wheels of cheese, human bones, and assorted viscera. This is how a cat would show affection if they could wield two axes. And, because Two-Axe was lacking in social niceties, anyone who said anything to him that could even possibly be construed as an insult quickly met the business end of his two axes.

Bethesda

Bethesda

I didn’t download an illiteracy mod that turned all the written words in the game into nonsense Kingdom Come: Deliverance style. I didn’t write a custom script that made it so every NPC was romanceable. I just decided to do all this and then did it. It was difficult, maybe even insane, but it was also some of the absolute most fun I’ve ever had playing videogames, ever. I realize that this might sound like apologia and that some may feel that if a game requires a bunch of self-imposed restrictions like a Nuzlocke run, the game itself isn’t fun. I would direct their attention to this actual tweet from the official DOOM account:

The Twitter equivalent of ripping a demon’s spine out of its mouth.

Because video games are games. Part of the fun of games is changing the rules. What, you’re going to tell me that your household doesn’t have a rule in Monopoly that if someone buys too many properties you can challenge them to a bareknuckle boxing match? Or that when your family has a Greased-Up Hog Wrestling Tournament the hog doesn’t have three tasers taped to him??? Enjoy your boring family get-together, I guess. (If you can even really call it Christmas without a few hog-tasing.)

There’s one other way the desire to eliminate the ‘play’ aspect from playing video games manifests itself, and that’s with overemphasizing efficiency. Is winning a game fun? Sure, but is it more fun than actually having fun? That depends on how happy your childhood was. Now I have this friend -- let’s give him a ridiculous made-up name, like “Paul.” Now Paul is a man of questionable opinions: he once told me that Stadium Arcadium is “the only good Red Hot Chili Peppers album” because “the rest are too funky,” just to establish the kind of person we’re dealing with. I once bought Paul the game Dishonored, one of my favorite games ever made. I asked him how he had enjoyed it and he said it was boring. I was shocked! Boring?! How can anything with that much neck-stabbing be boring? As it turns out he had played the game like an FPS and just blasted every single enemy with the pistol. Which...I mean, I guess you can technically beat the game that way, but did you really play the game? The fun of that game is figuring out all the batshit ways you can combine powers to break the game. The joy is in the experimentation, not the destination.

I’m not trying to say that anyone who says a game doesn’t have enough content to justify its price is wrong -- I’ve definitely felt that way! The story mode for Pantygun Panic VI: Super Edition: Let’s Go Girl’s Dormitory!!! had character arcs that frankly fell a little flat. I’m just saying that part of what makes games such a compelling medium to me is the way the experience of playing them can be unique to the player.

It’s one of the most important distinctions between games and films, with the other big distinction being “mostly everything.” Because:

No, Games Aren’t Becoming More Like Movies

The idea that games are becoming more and more like movies is a weirdly common complaint. Because it’s completely wrong, but also kinda right for the wrong reasons -- like someone (NOT ME) saying Bigfoot doesn’t exist because ‘nothing that sexy could be real.’ When people say that games are becoming “more like movies,” it’s somewhat nebulous -- it’s an accusation that’s been leveraged against games for many different reasons. The Uncharted games were often, in their time, said to represent the filmification of games. Except that that’s completely wrong! The Uncharted games clearly take a lot of stylistic direction from adventure films, but what people seem to be upset about is that the games embrace cinematic grammar (in particular, the grammar of invisible Hollywood editing of pre-2000s cinema). But virtually all visual media employs filmic grammar for the same reason this article was written using the Roman alphabet and not bloodlgyphs of my own devising -- because the audience already knows and understands the former (and the latter might accidentally summon Kyzgylr the Soul Ravisher).

Modern society is so mediated that we absorb the semiotics of film pretty much from birth. There are literally television shows made for babies, like Teletubbies and Baby Einstein and a third show. (You were probably expecting me to end that sentence with a third show ostensibly aimed at adults that’s treated by its fans as a work of art so profound it makes Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire look like YouTube’s Dog Farts in Own Mouth that’s actually not good. It turns out there is no such show. Please hire me in your writer’s room.)

It makes sense that games would adopt the language that cinema spent a century cultivating. Even if you don’t know the fancy film school terms, you understand the semiotics. Let me give you an example. Let’s say you turn on a short film and see this:

Via Memebase

Now clearly, that is hilarious. But then the next image you see is this:

Suddenly the chimp with a gun takes a darker turn. Why is he aiming it at Tsar Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov? Has Comrade Bananovich suffered enough at the hands of the bourgeoisie? Were his lands ravaged by cossacks? Does he just really hate ostentatious epaulets? We don’t have an answer because this is clearly insane, but if you were shown these two clips in succession you’d assume that chimp was aiming that gun at the Tsar and that there’s a relationship of meaning there. If instead of the Tsar it was a man holding a banana, the emotion of the viewer would change again, probably to assume that man was being robbed at gunpoint for his delicious ‘nanner. This is called the Khuleshov Effect, but I’m guessing that you didn’t need to read Towards a Theory of Montage to know that when you see two images on a screen in succession you assume they’re related somehow.

So yes, games do sometimes adopt cinematic language. But that doesn’t make them like movies. The Uncharted games aren’t really like movies because there are still lose conditions and interactions can change every time. Let’s say Nathan Drake is about to kill thirty people who are foreign enough to seem scary and different but white enough that it doesn’t feel racist to murder them all -- probably Russians, another element the games borrow from the film industry. You could use a stealth approach, go in guns blazing, try to lure them all to the inexplicable red barrels that Video Game World always seems to have around as a convenient explosion container, or do any number of things. And, if you’re me, you’ll probably have to do it several times because the heavy enemy keeps catching up to you and snapping your neck which is SO CHEAP it’s BULLSHIT why would they MAKE IT LIKE THAT, screw this I’m gonna play Katamari Damacy. So where it counts, it’s still a game. As far as I know there’s no such thing as a movie that stops at certain intervals and tests your abilities to watch movies before letting you see more.

When people say games are becoming more like movies, they sometimes mean that a larger percentage of time spent engaging with a game is spent watching cutscenes. Which...is not really a new phenomenon. The PS2 game XenoSaga Episode 1: Der Wille zur Macht has around fifteen hours of cutscenes. I’ve never played that game, but I’m shocked they were able to squeeze that much plot out of Nietzsche piloting a big-ass robot which he will use to find and kill God. Not to prove his philosophy correct in a literal sense, but because it’s a JRPG and killing god is just how they do. If anything, it seems like the trend in games has been towards integrating plot more into gameplay than just giving huge infodumps (Nota Bene: an “infodump” is also where you read a bunch of Wikipedia articles on the toilet, also known as “doing research for this article.”).

With the possible exception of Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, most FromSoftware games deliver their plot in breadcrumbs, atmospheric details, and making players take a break after dying to Sir Alonne for the 216th time to browse lore theory forums to prevent a rage-induced aneurysm. Or maybe that last one is just me. But I would argue that games drip-feeding plot and world-building details through an explorable environment is actually evidence of games transcending filmic grammar and developing a language of their own. It’s part of what makes games magical. Which brings me to my final point:

We Need to Be Talking About Punctum

In film theory, there are related concepts called ‘affect’ and ‘punctum.’ How exactly do you define them? Ask ten different film theorists and you’ll get thirty different answers. Roland Barthes, the photographer and essayist who coined these terms, said that punctum is the element of a photograph that wasn’t intended by the photographer. That’s not really useful for our purposes here because, barring unintentional glitches or unforeseen ways mechanics interact, EVERYTHING in a game is there on purpose. But he also defines punctum as the way that photographs can influence discrete observers differently -- that is to say, the inexplicable things in visual media that really resonates with us for reasons too personal or inscrutable to truly communicate. It’s the things that reach out and penetrate the anuses of our souls. When Harry from Harry and the Hendersons first came on screen, I can’t explain why I wept at such beauty or the fury I felt that he couldn’t exist in our world.

If it sounds like I’m talking about magic, well, I kind of am. I’m a firm believer that, in a conversation about art, we have to eventually talk about our subjective experiences of beauty. Video games are a medium in their adolescence -- and, like all adolescents, there’s an element of resentment at not being taken seriously. Roger Ebert famously wrote that games can’t be art, but he also once wrote that “Ere this night does wane, you will drink the black sperm of my vengeance!”, so, you know, everyone is wrong sometimes. Video games, like mainstream film, are both a work of art and a commodity. There’s a desire in the world of games for games to be appreciated as art, but if that’s what we want, we need to be talking about games as art.

When talking about videogames, there’s a kind of cold cynicism that’s really unbecoming for discussing a work of art. I understand where this impulse comes from -- really, I do! If you’re on federal minimum wage a PS5 game will cost you roughly ten hours of labor -- more than a day’s work. That’s a lot to gamble on a game that might suck. Seventy bucks is a lot of money to shell out for an artistic experience that might enrich your soul or might leave you angry that you didn’t instead buy seventy $1 burritos. But with as much was spilled around the release of Bioshock, you’d think the criticism around videogames would have matured a little more. I’m certain there are niche YouTube channels really engaging with the material, but it seems like virtually all mainstream game criticism writes like they’re reviewing a blender. Surely, when talking about the worth of a game, there’s more of a balance to be struck between getting your money’s worth and the way a work of art made you feel? Like with film, this is all complicated by what the media in question is trying to be. Pacific Rim didn’t give me a deeper understanding of the human condition but it did show me kickass robots fighting awesome monsters and that totally ruled, and there’s value in that, too. And Super Mario Odyssey didn’t help me reconcile with my own mortality, but it did provide me with razor-sharp platforming glee that was exemplary of the form.

For me, the fun gameplay aspects of a game are forgotten fairly quickly. What persists is the memory of how a game made me feel. Let me give an example. Perhaps you’ve seen some of the coverage of the game Cyberpunk 2077. Now, to be fair, I played the game a few months after release when some of the worst bugs had been fixed, and it was still an absolute buggy mess. It crashed constantly. The skill levelllng system was so unbalanced that despite doing literally every single piece of content I never reached the max level in a single skill, which is necessary to unlock the most powerful abilities. The difficulty was bizarre -- normal difficulty made enemies bumbling paper-skinned buffoons reduced to quivering wet meatpiles by a single cyberbullet, while the next difficulty notch up forced me to invest a crapload of skillpoints into the skilltree that raised health and reduced damage simply so I could survive fights long enough to see where the enemies even were. Thematically, the game felt more afraid of commitment than the first act male love interest in a 90s rom-com. Like all cyberpunk, the world is clearly an indictment of capitalism, but several times the game goes out of its way to explicitly remind you that maybe capitalism isn’t an inherently predatory system? Johnny Silverhand tells you directly that his act of nuking the headquarters of a war-profiteering corporation “isn’t because capitalism is a thorn in side.”

But you know what else? I also really, really felt like I was walking through another world. That first time I walked out of V’s apartment into the street, I felt like I could smell Night City. Driving through the city at night, neon signs racing past the window, listening to nightmare hiphop about Night City before leaping out of my car and setting gang members on fire with my mind...man, that was some punctum. The game has some of the most interesting metatextual commentary on agency I’ve ever seen in the game. I won’t spoil it here, but the scene that takes place in a ratty motel after a critical mission left me with a miniature existential crisis. It has a story that soars at its highest points and some incredible characters with conflicting needs, neuroses, and internal struggles. Also one time my dick completely disappeared.

CD Projekt

The point is, of the pages and pages on the subject of Cyberpunk 2077 that I read, almost none of it engaged with the text on a critical level. And, again, I understand why! Games are expensive, and the bare minimum we as consumers should expect is functionality. People should know about the weird difficulty, the obnoxious skill levelling system, and that it reduced my once-grievous schmeat into nothing more than a warm, featureless, lightly-pulsating fleshmound. But there’s a lot of interesting stuff going on in this game that doesn’t deserve to be completely discounted by the flaws in the experience.

Ultimately I believe that we need to open ourselves up more to the magic of the medium. It may sound counterintuitive, but part of my maturation as an enjoyer of art came when I ceased being a cynical consumer and recaptured a wonderment that is usually seen as being the purview of childhood. The film theorist Murray Pomerance once said that we should come to film not as critics but as lovers. Not only would that enrich our experiences as consumers and critics, but it’s my hope that ultimately it would lead to a deeper appreciation for video games as a medium.

And then, on that joyous day, we will all be as transcendentally beautiful as a sexy, sexy Sasquatch.

William Kuechenberg is a repped screenwriter and Nicholl Top 50 Finalist looking to get staffed -- or to write on your videogame! He is also 50% of the podcast Bad Movies for Bad People, the world’s FIRST and ONLY comedy podcast about movies (available on all major podcast platforms!). He is on Twitter.

Top image: CD Projekt